You’ll Never See Me Again

“… There were the four of us walking along the dirt road in April of 1924, from Barangay Pañgada to Vigan, the capital of the Province of Ilocos Sur [Philippines]. I was carrying a little bag of clothes and 180 pesos in my pocket…The 180 pesos was the money I was given to start my life in Hawai’i as a contract laborer in the plantations…I was seventeen years old and didn’t know anything about leaving home…My father said he would let me go, but my mother didn't want to and cried when she first found out, ‘If you go, you'll never see me again!’ She was right; I never saw them again after that day in Vigan, when I got on the truck with the other young Ilocano boys for the ride to Manila. …” Sergio Ragsac

Glittering Streets of Gold

In the 1920s, young Pinoy (Filipino) men began emigrating to Hawaii and the mainland, drawn by offers from plantation owners and the promise of education and employment. Most of the early arrivals to the mainland were students, such as those who formed the Filipino Club at San Jose State Teachers College in 1923. They had an advantage over their Chinese and Japanese predecessors in that they were U.S. nationals (the Philippines was a U.S. territory), and no passports were needed. But like their Asian counterparts, they found themselves subject to prejudice, intolerance, and hardship. When work was found, it was for low-paying, menial positions such as farm workers, houseboys, bellboys, and kitchen helpers. One early immigrant to the Valley, Jacinto Siquig, reflected, “…I couldn’t make a go of it…Every book I’d read said gold was glittering on the streets, but when I got here…[he laughs]”

Farm Workers

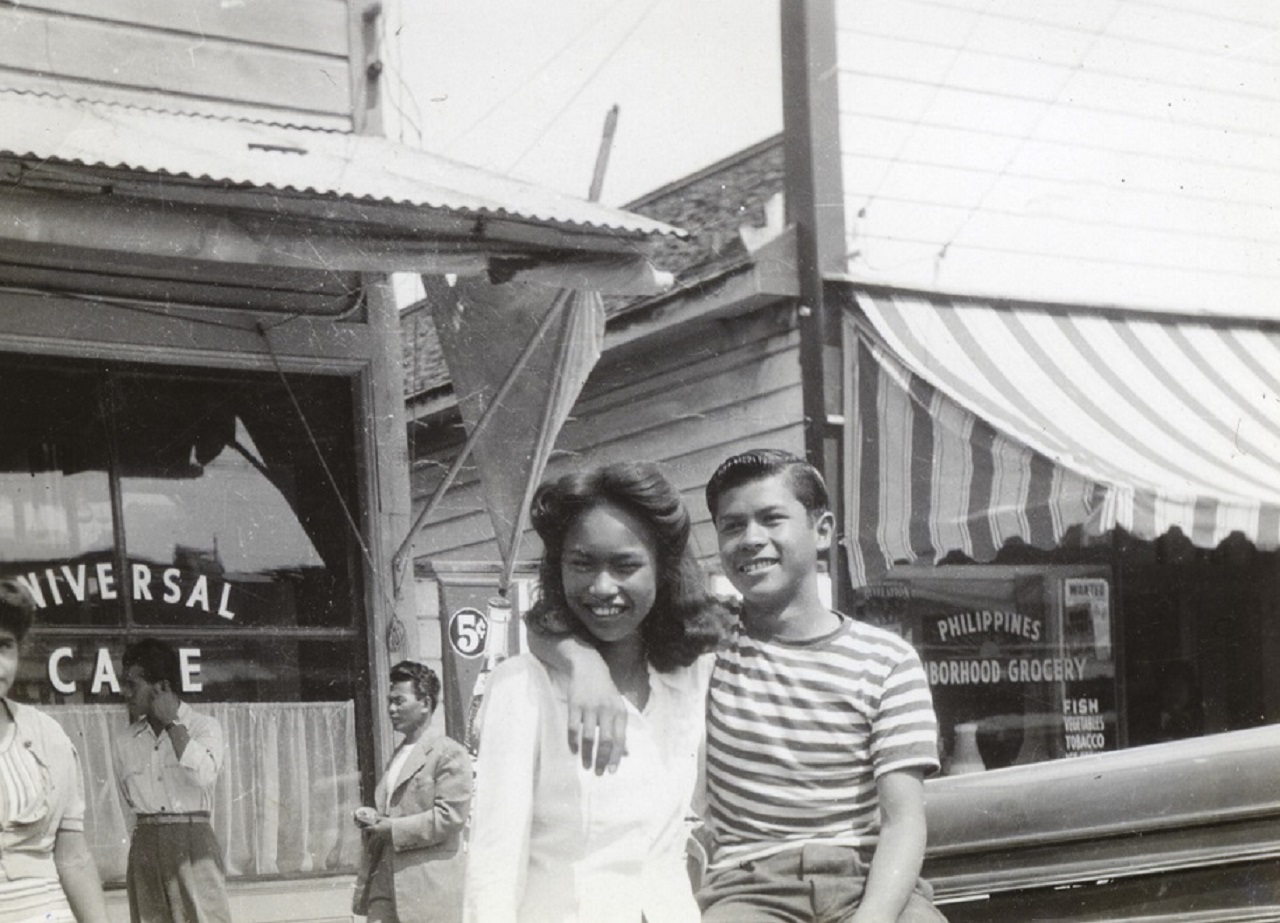

The first generation, also known as the Manong generation, often found work on farms along the Pacific Coast. As agricultural work was seasonal, many would follow the crops up and down the coast. Many Filipinos were drawn to the Santa Clara Valley, though their numbers were concentrated in Stockton, especially in the Spring for the cultivation of asparagus. In 1920, the U.S. census counted forty-five Filipinos in Santa Clara County. By 1930, this number had grown to 857. In 1940, Stockton had the largest Filipino population outside of the Philippines, with over 10,000 during harvest season, while the number in the state at the time was over 30,000. There were few women in the first wave of immigrants. It wasn’t until the second wave after WWII that more women and families were able to immigrate. A third wave began in the late 1960s.

Pinoytown

Like the early Japanese immigrants that preceded them, Filipino immigrants were drawn to San Jose’s Heinlenville Chinatown. By the early 1930s, a number of Filipino businesses and organizations began appearing within this growing Asian community, primarily along North Sixth Street between Jackson and Taylor Streets. The Filipino community was particularly active in this area during WWII, though even with the loss of many businesses on the east side of the street, three properties were joined and remain in the hands of the Filipino community to this day. Efforts to preserve the history of the Filipino enclave in this area has resulted in the coining of the term Pinoytown by local historian Robert Ragsac. The Filipino community’s presence is also represented with the Jacinto “Tony” Siquig Northside Community Center and the adjacent Mabuhay Court senior housing.

Exhibit and Special Event: Pinoytown Rising: Filipino Americans in Santa Clara Valley

Further Reading from the California Room:

- Pinoy: The First Wave by Dr. Roberto V. Vallangca

- Pinoytown Virtual Tour

- San Jose Japantown: A Journey by Curt Fukuda and Ralph M. Pearce

- Filipino Americans: Forever Our Legacy FANHS

- Video: Pinky Reintar on the Filipino Boarding House and Dimas Alang Hall in San Jose

- Video: Pantoc Association Meeting, Filipino Community Center, San Jose

Add a comment to: Looking Back: Filipino Americans in Santa Clara Valley