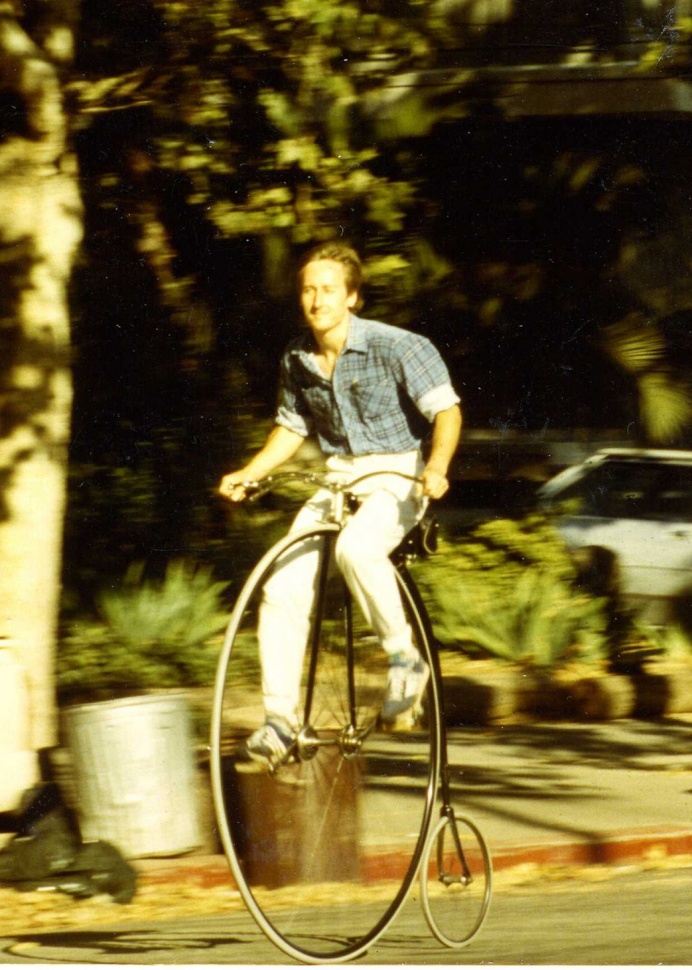

Seeing a Tall Bike for the First Time

In the 1960s, my mom had a small sculpture of a man in a top hat riding a high wheel bicycle. It sat in our kitchen window for years, and I was fascinated by the idea of a bike with such a large front wheel and such a small back wheel. Then sometime in the mid-1980s, I saw one for the first time. It belonged to Dave Wood, a fireman who lived in a nearby neighborhood. I couldn't believe how beautiful it looked with it's huge wheel with spokes that radiated out like rays of the sun.

A Brief History of the Bicycle

The first bicycle was invented about 1817 by Baron Karl von Drais. Made primarily of wood, it was two-wheeled and steerable, though it had no pedals. Improvements to this design were made over the years, then in 1869 Frenchman Eugene Meyer invented a wire-spoke tension wheel, and began producing high wheel bicycles. About 1870, James Starley in Coventry, England further improved the design, and began producing a high wheel named “Ariel.” Production and popularity took off in England at this time, with interest in France beginning around 1875. The U.S. began importing English high wheels in 1877, and American manufacturer Albert Pope gained control of applicable patents and began production of his “Columbia” high wheel bicycles in 1878. High wheels (commonly referred to as “ordinaries”), were also nicknamed “penny-farthings” in England because the wheels resemble the British penny and farthing coins (the former being much larger than the latter).

In 1885, John Starley (James Starley’s nephew), produced the first successful “safety bicycle” called the “Rover.” It featured equally sized wheels with a chain-driven rear wheel. This was a significant improvement over the high wheel design, as it eliminated the danger of being pitched over the handlebars, allowed freer steering of the front wheel (no longer influenced by the pedals), and gave greater riding access to women and children. Though availability of the high wheel bicycle continued through about 1892, it was largely replaced by the safety by 1890. This new design became the basis for our modern bicycles, along with numerous improvements like pneumatic tires.

My First High Wheel Bike

In the Jan/Feb 1986 issue of Antique/Classic Bicycle News I found an ad for high wheel bicycles. Writing to a fellow named Madison Edgerton in New Jersey, I was offered my choice of a 51" or a 52" (front wheel height) Columbia high wheel. I chose the 51" Columbia Light Roadster due to its lower price ($1,250). I picked the bike up at the Yellow Freight Shipping dock, took it home, unpacked it, and immediately tried to ride it.

Learning How to Ride

After cutting the bike out of it's cardboard container, I positioned it between my truck and the laundry room of my apartment building. Using the running board of my truck, I cautiously climbed up into the seat. Whoa! It feels pretty high up there. These were the days before the Internet and Youtube instructional videos, and I hadn't gotten any tips from Dave Wood or even watched how he got on and off his bike. Timidly pushing off from the truck I pedaled slowly forward, too slowly in fact and I soon fell against the laundry room wall. I knew then that I just needed to get my courage up and use the little step above the back wheel. Putting my left foot onto the step, I pushed off to gain speed like you would a skateboard, then lifted myself up into the seat and began pedaling.

I rode most of the way down the long driveway, then decided to get off. I tried getting off like you would a regular bike and immediately fell to the ground. The problem was that the pedals don't coast in place like a regular bike, but keep turning. Neither I nor the bike were hurt, so I tried it again, but this time I hopped off the back while keeping hold of the handle bars. The "proper" way to dismount is to reach back for the step and reverse the mounting process, though I prefer a more immediate dismount. This "emergency" dismount method of hopping off the back is handy in the event of sudden obstacles (dogs, children, etc.) that could otherwise cause me to tumble over the top of the bike (known as a "header").

A Long and Winding Road

One hot summer day in 1986, I decided that it would be a great idea to ride my yet un-restored high wheel down to Morgan Hill and back. I'd done this for years on my ten-speed, and I figured that it shouldn't be too hard. I headed south on Almaden Expressway, then continued on McKean Road passed Calero Resevoir. I continued south and then left onto Watsonville Road to Morgan Hill. It was a fun ride (with some walking on the steep parts), but once I made it to Monterey Road I was sunburned and dehydrated. I was too wiped-out for the ride back, so I called my dad to come down and pick me up. My total distance covered was about 28 miles. I eventually restored the bike with the help of Bill Hyland of Hyland Family Bikes and Desimone's Cycles. Desimone's mounted the tires using the gray rubber that was normally used for wheelchairs. The rubber comes off a spool and has heavy gauge wire running through it.

A Second High Wheel Bike

My second high wheel bike was a 54" Columbia Expert (pictured above). I purchased it from an antique shop in Pennsylvania. Like the Light Roadster, it was rideable, though also in need of restoration. The primary safety concerns are the condition of the spokes and the tires. After that, the focus is on rust, lubrication, and proper adjustment of bearings and various nuts and bolts. This bike didn't need much work, though a disappointment came when I realized that the spine and the forks were mismatched. On a Columbia, each should have matching serial numbers stamped into them, and mine were both different. Before restoration, these bikes can need just about any part like spokes, tires, seats, rear wheels, pedals, brake parts, even handlebars. The two most critical parts that should be healthy and matching though, are the forks and the spine. This is not to say that non-matching parts are without value, because even reproductions can cost a pretty penny.

A Third High Wheel Bike

I purchased my current high wheel bicycle on Ebay in 2015. It was a pretty rough "barn find" with modified 10-speed pedals and a seat made out of plywood, padding and baling wire all wrapped up in electrical tape. The rear wheel was from a kids bike with a garden hose tire, and the mounting step was a flimsy piece of sheet metal. Although there was a lot of work to be done, most of the critical components were there. Through online research and an organization called The Wheelman (also on Facebook), I was able to determine that I'd purchased a 52" 1887 Gormully & Jeffery (G & J) American Challenge.

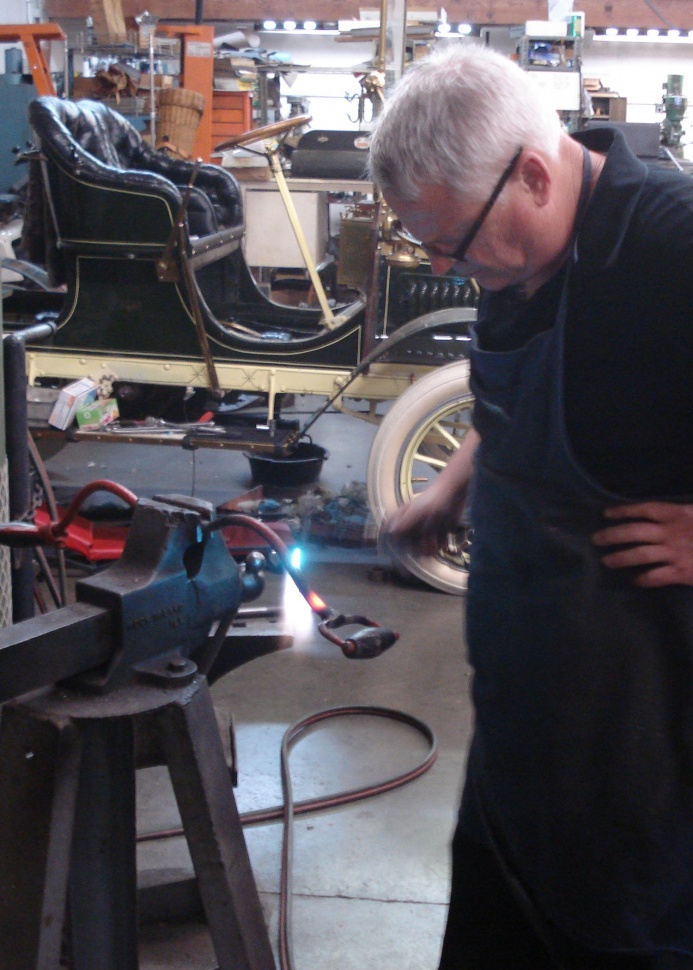

Restoring A Gormully & Jeffery High Wheel

I've been restoring my latest high wheel over the course of the last five years, and I've relied on the assistance of a number of talented people. One person who has played a central role is Tom Holthaus of Quality Machine Shop in Santa Clara. Tom is very experienced with turn-of-the-century vehicles and early motorcycles. He's also had a couple of high wheels and is great at replicating parts. Tom straightened the handlebars and rear forks, and replicated a brake handle and step mount.

Another key contributor was Craig Allen in New Jersey. Craig provided a beautiful pair of exact reproduction pedals, and detailed patterns that Tom used in creating missing parts. Craig also sent me a seat pattern with detailed instructions which allowed me to create a beautiful new seat.

My final challenge in getting the high wheel ridable again, was to get the wheels trued (proper spoke adjustment) and new solid rubber tires installed. I called upon Alex LaRiviere, the former owner of Faber's Cyclery on First Street. Alex had trued and installed new tires on my second high wheel in the early 2000s. Alex agreed and did a great job with it.

Others who contributed were my friend Matt Shuster (Ironwood Designs) who carved beautiful new walnut hand grips with his CNC router, Greg Barron (Rideable Replicas) who supplied spokes, tire rubber and a rear rim, Bill Warwood with spoke threading, Fred at Valley Plating, Superior Chrome (now closed), Chuck at Bicycle Express, and Dave at Santa Clara Powder Coating.

More Reading from the California Room:

- The Valley's Love Affair with the Bicycle by Ralph M. Pearce

- Sourisseau News: “Valley’s Love Affair With the Bicycle” a video based on the album by Ralph M. Pearce

- A History of Bicycle Track Racing in San Jose: The Burbank Velodrome Years by Tracy Ann Delphia

- Collecting and Restoring Antique Bicycles by G. Donald Adams

- California Room Index: Bicycles

Add a comment to: Looking Back: Riding High on an 1880’s High Wheel Bicycle