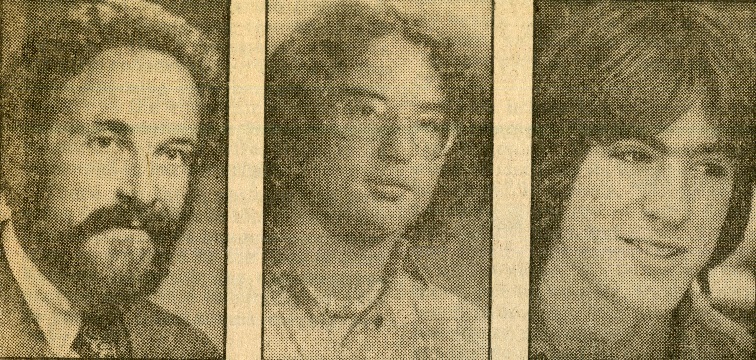

It was November 1975; disco was at its height, flared pants abounded, and the United Nations had just adopted General Assembly Resolution 3379, condemning Zionism as a form of racism. High schoolers Michael Robins and Ira Marcus (students of San Jose’s Temple Emanu-El) and their teacher, Roberta Bell-Kligner, composed a petition protesting the UN resolution. On November 16, Robin and Marcus set up a table in the courtyard of Campbell’s Pruneyard shopping center (then just five years old) to collect signatures.

Security guards arrived and asked them to leave, and they complied. Shortly thereafter, they contacted the management of the Pruneyard requesting permission to resume petitioning, and offering to comply with any reasonable restrictions. When management refused, they decide to take their case to court.

Represented by San Jose Lawyer Philip L. Hammer, the plaintiffs sought an injunction from the Santa Clara County Superior Court. Judge Homer Thompson upheld the shopping center’s right to maintain its policy. They next petitioned the 1st District State Court of Appeals, but the appellate judge upheld Thompson’s ruling. It wasn’t until four years later, when the case reached the California Supreme Court, that they were finally victorious. On March 30, 1979, in a 4-3 decision, the Court overturned the Thompson ruling, stating that shopping centers were bound by the California constitution to permit free speech on their premises, with reasonable restrictions of time, place and manner. The court’s reasoning was consistent with a 1970 California Supreme court decision affirming citizens’ rights to petition at a San Bernardino shopping center.

Article 1 of the California Constitution states that “Every person may freely speak, write, and publish his or her sentiments on all subjects. A law may not restrain or abridge liberty of speech or press.” This language goes beyond the U.S. Constitution, which does not affirm free speech rights, but merely forbids the government from infringing upon them.

However, the California Supreme Court’s philosophy ran contrary to that of the SCOTUS. In the 1972 case of Lloyd v. Tanner, the SCOTUS concluded that, since shopping centers were private property, an Oregon mall was at liberty to bar people from passing out literature opposing the Vietnam War, provided that “adequate alternative avenues of communication” were available.

The Pruneyard’s lawyers, hopeful (perhaps due to the Tanner ruling) that the federal government would see things their way, appealed to the SCOTUS, and the two sides geared up for the final showdown.

The U.S. constitution empowers the states to grant citizens whatever rights they see fit, so long as those rights do not run counter to those guaranteed by the Bill of Rights. It was on the basis of the affirmative free speech rights of the California Constitution that Hammer argued to the SCOTUS that the California Court had been within its rights to countermand the precedent established in Lloyd v Tanner. He further argued that since shopping centers often intentionally established themselves as community gathering places, they were obligated to adopt the rules that govern the public square.

The Pruneyard’s lawyers maintained the case was not about free speech at all, but about the federally protected right to control ones property. Why, argued Pruneyard counsel Thomas P. O’Donnell, should a state’s free speech rights weight more heavily than federally appointed property rights? O’Donnell invoked the 5th and 14th Amendments, arguing that the California Supreme Court’s ruling amounted to the state compelling property owners to use their property “as a forum for the speech of others”.

The SCOTUS didn’t buy O'Donnell's argument, however; on June 9, 1980, the justices ruled unanimously in Robins’ favor, concluding that the plaintiffs' peaceful exercise of their free speech rights did not violate the owner’s property rights. In his opinion supporting the decision, Justice William Rehnquist stressed the public nature of the shopping center. Justice Thurgood Marshall called the court’s decision “part of a very healthy trend.”

Pruneyard Shopping Center v Robins remains a contentious decision, and protesters have been testing its fuzzy boundaries since it was decided. In keeping with the provision that reasonable time place and manner restrictions may be imposed, many shopping centers have attempted to outline rules for protest and petition, often ending up in court. In Fashion Valley Mall, LLC v. National Labor Relations Bd. (2007), for example, the California Supreme Court applied Pruneyard as a precedent in its ruling that a San Diego shopping center could not prevent unions from boycotting its tenants on its premises. Dissenting to the majority opinion, Justice Chin wrote: “Pruneyard was wrong when decided... Private property should be treated as private property, not as a public free speech zone… It is wrong to compel a private property owner to allow an activity that contravenes the property's purpose." This echoed the arguments of Pruneyard’s lawyers decades earlier.

In Ralph’s Grocery Co. v. United Food and Commercial Workers Union Local 8 (2012), the California Supreme Court opined that: “to be a public forum under our state Constitution's liberty-of-speech provision, an area within a shopping center must be designed and furnished in a way that induces shoppers to congregate for purposes of entertainment, relaxation, or conversation, and not merely to walk to or from a parking area, or to walk from one store to another, or to view a store's merchandise and advertising displays.” This ruling refined the concept of a public forum not fully fleshed out in the Pruneyard decision, narrowing the scope of Pruneyard to shopping centers with areas that served the purpose of, or could be likened to, public squares--- bad news for would be petitioners! Still, California still takes a more liberal view of the Pruneyard decision than most other states.

In his debate-sparking essay Can Free Speech Be Progressive?, Georgetown University law professor Louis Michael Sideman boldly contends that speech rights and property rights are not separable concepts. “Speech,” Sideman argues, “must occur somewhere and, under modern conditions, must use some things for purposes of amplification. In any capitalist economy, most of these places and things are privately owned. …Because speech opportunities reflect current property distributions, free speech tends to favor people at the top of the power hierarchy… ...While it may be cheap to produce speech, aggregation and amplification… require capital.” Dissenters to the Pruneyard decision feared the opposite effect- that the case would set a precedent by which capitalists would become thrall to citizens, and transform “privately owned commercial property into public forums”.

The Mercury News’s H. Bruce Miller called the clash between property rights and speech rights, “one of the most important conflicts of our times”. Indeed, disputes over free speech and property rights have only heated up over the last four decades, and are more contentious today than ever, with the nation divided on the issue of corporate speech rights as addressed by Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc. (2014), and most famously, Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (2010). For many, the underlying philosophical question remains unresolved; where should property rights stop and public rights begin? It all depends on who you are, where you’re sitting, and what you have to say.

Check out the California Room's Mercury News Clipping Files and SJPL's Library databases for more free speech history!

References

- Stell, J. (1985, February 20th). How the Pruneyard Rose, San Jose Mercury News.

- Miller, H. B. (1980, March 16th). Property Rights vs. Public Rights, San Jose Mercury News.

- Author unknown. (1972, August 24th). Prune Yard Tower Overlooks Unique Shopping Environment, Los Gatos Times-Saratoga Observer.

- Sideman, L. M. (2018). Can Free Speech be Progressive?, Columbia Law Review, Volume 118, No. 7.

Quoted Cases

- Pruneyard Shopping Ctr. V. Robins, 447 U.S. 74 (1980)

- Ralph's Grocery Co. V. United Food & Commercial Workers Union Local 8 (2012) 55 C4th 1083

- Fashion Valley Mall, Llc V. National Labor Relations Bd. (2007) 42 C4th 850

- California Constitution, Article 1, Declaration Of Rights [Section 1 - Sec. 32]

Add a comment to: Free Speech in Silicon Valley: Pruneyard Shopping Center v Robbins